By Loren Michael Mortimer - What does it take to leave one’s homeland in search of an uncertain future? Why do entire communities migrate to faraway lands in ways not explained by rational self-interest? Such questions have long intrigued David Kyle, associate professor of sociology and founding member of the Temporary Migration research cluster at UC Davis. In a recent paper, he offers some potential answers.

Kyle’s cutting-edge research reveals how the socio-cognitive process of imagining oneself inhabiting a physical destination—prior to the physical move—affects migration behavior. Kyle and his co-author Saara Koikkalainen call this mental process cognitive migration. Their research helps us to understand why some people migrate during times of war, famine, and economic hardship, while others choose to stay.

Temporary migrations have loomed large in recent headlines, from the wave of immigrants to the United States from Latin America and China, to the ongoing Syrian refugee crisis. While empirical researchers have long considered economic, social, and cultural forces driving migrations, they have paid relatively scant attention to the myriad choices migrants make that may not be experienced as formal decisions.

Bringing the body along

Kyle began to think about the nature of the underlying mental and social processes that may lead one to migrate. Each migrant has his or her own story as to why they decided to embark on a life-changing journey; before any individual departs, they typically experiment with the decision many times in their minds, imagining a different future in a distant land.

“I kept coming back to the notion,” Kyle explains, “that many of our big decisions may be best described as the ‘mind’ moving many times over before we bring the body along, thus often making the actual move only a single step in a much longer and more complex process than we have allowed. However, this is not a purely psychological process of individual brains, but rather best described as the intersection of cognition and culture.

“A migrant doesn’t just imagine a new life abroad but actually begins a cognitive resettlement before the move and even before a decision to leave.”

Crossing the mental threshold

Humans are hardwired for imagination. As an evolutionary adaptation, the ability to imagine future outcomes, and to cognitively locate the body in different places and times, enabled humans to not only populate the entire globe—including distant Pacific Islands—but also to adapt and thrive in their new environments.

The process of cognitive migration is characterized as mentally experimenting with the physical, social and emotional details of a specific future time and place. Just as ancient Homo sapiens imagined futures for themselves outside of Africa 150,000 years ago, we can plausibly imagine a future human colony on a distant planet like Mars. The underlying cognitive process remains the same, even though the social, cultural, and technical contexts could not be more different.

Migration is not a mere question of imagination, Kyle says. “The concept of cognitive migration is an attempt to sensitize us to the crossing of the mental threshold in which we begin to move from mere imagination to making a place feel real.”

Avoiding loss

One of Kyle’s most surprising findings—though building on the work of a range of scholars—is that, rather than seeking to remake themselves through migration, humans seek familiarity in their new locations. A major part of the cognitive migration process is about avoiding loss, not just acquiring something better. The time, place, and manner of migration largely depend on what qualities an individual wants to retain rather than replace.

“It’s a truism that we take leaps based on perceptions of a future change in status we find desirable,” Kyle says. “But for most of us, a particular adventure is perceived as compelling only as long as we get to keep those things we value from the origin location, and don’t have to sever our ties and identities.” The Pilgrims, for example, did not venture to the New World in 1620 to become “new” Americans. Rather, they migrated in order to practice their existing religion and live according to established English customs.

Asking new questions

Cognitive migration offers important new research possibilities within the interdisciplinary scholarly field of migration studies. Historians, economists, demographers, geographers, and other social scientists approach the subject of mobility with a remarkably diverse methodological tool kit. Using cognitive migration as a theoretical frame, empirical researchers may now ask new questions about how the alternative futures imagined by an individual can influence future migratory behavior.

Kyle posits that future empirical research should “focus on those who do not take the path under consideration without assuming a ‘choice’ was made or considered and foreclosed.” He believes that UC Davis is uniquely suited to take up such research questions because the numerous scholars engaged in migration studies “creatively combine traditional and innovative methods—often exploring new technologies of inquiry, such as various kinds of big data generated by cellphones or massive digitized archives—or seek collaborations and ideas that are much more diverse than those of the past.”

Imagining futures

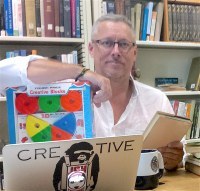

Kyle’s own research on cognitive migration has already inspired a book-length manuscript (co-authored with John Dale, associate professor of sociology at George Mason University), under contract with Stanford University Press. The book explores the social history of the idea of creativity.

“We live in a world in which imaginative leaps of logic and their rapid realizations—no matter the externalities—are encouraged widely as a kind of normative Zeitgeist,” he says. “And yet, they are riskier than ever for those not already part of a new managerial elite, or at the controls of the digital dashboards. I find this fascinating, a little frightening, and an historical oddity to be understood.”

In imagining potential futures, Kyle wanted to understand how some people can fail catastrophically and still claim success as innovators, while for the majority of people even a small stumble on a career path can be devastating. How did this emerge over the past two centuries? What might it mean for the knowledge that comes out of this system, and for our quality of life? Kyle hopes to find out.

As the twenty-first century unfolds, he wonders to what extent "‘machine talent’ will alter or deepen these cognitive cultures of creative capitalism that seem magical, and, nonetheless, perfectly functional with high levels of inequality.” Kyle and Dale frame their research as an “archeology of the present” that will, in turn, help social scientists and others better understand the cognitive processes animating inequality in contemporary society.

Learn more about David Kyle at his faculty webpage. To read Kyle and Koikkalainen's article on cognitive migration, visit the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies website.