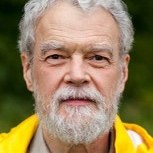

By Phyllis Jeffrey - With new physical evidence appearing every day, why does climate change remain a subject of contention, confusion—even flat-out denialism? Approaching climate change through collective orientations toward time and imaginings of the future, Research Professor of Sociology John R. Hall seeks to shed light on the sociological side of the climate change conundrum.

Hall began to grapple with the topic of climate change a few years ago, after being invited to take part in a special panel discussion on the topic of “social futures.” In his view, climate change—involving as it does powerful economic interests like the fossil-fuel industry, along with all of our familiar modes of life—transcends the “strategic” world of politics and eludes simple policy prescriptions.

On one hand, it is a process that Americans (at least, until recently) have yet to experience as full-fledged crisis—a situation Hall likens to that of the proverbial “frog in a pot of slowly heating water.” On the other, it is a future that will involve changes we don’t like to contemplate.

“Fundamentally,” Hall says, “I don't think we’ve come to terms with the question of how deep a change in our way of life globally would be required to somehow ameliorate the consequences of climate change. Or, failing that, what we are going to do in terms of remediation.”

Four domains

In a recent paper entitled “Social Futures of Global Climate Change: a Structural Phenomenology,” Hall identifies four different social-institutional domains with regard to climate change. These are: climate science and policy analysis; conservative denialism; geopolitical security; and environmental activism. He examines how domain-specific relationships to registers of temporal action shape attitudes to climate change. In this approach, a lack of consensus cannot be explained as simply a struggle over political aims because doing so requires assuming that all actors view climate change in politics’ strategic register—that is, as power struggles over future advantages.

"It's like hearing the roar of the Niagara Falls before you reach it: you should maybe listen to it and take heed."

But not all actors seek a political solution. Hall highlights “the very radical differences between bureaucratic action in diachronic time and military or game or competitive action in strategic time, versus the sort of ritualized sacred time that is achieved in the community.” Thus, he adds, “different kinds of temporality have very different social logics to them.”

When it comes to climate change, we can understand ideology in social reality and collective action. “It allows us to make sense of how different social groups are positioned in relation to climate change because it allows us to deconstruct their ideological framing of who they are and what they’re about.”

Tipping points and security threats

Hall describes the work of climate scientists as grounded solidly in the diachronic register: the time of bureaucratic action, broken up into measurable chunks that may be represented on a calendar. Past, present, and future trends are written of in standardized units (years, millennia, etc.), with statements about the future (for instance, the net temperature increase in degrees since the industrial period) qualified with degrees of confidence based upon past trends.

This approach enables climate scientists to maintain legitimacy as neutral authorities. When discussing irreversibility or “tipping points,” however, climate scientists must remain circumspect in assigning calendar dates to “apocalyptic” phenomena. For instance, during recent news that we had passed the “carbon threshold” of 400 parts per million in the atmosphere, scientists were at pains to counteract the alarmist headlines that ensued.

“The scientists themselves,” notes Hall, “hasten to point out that 400 parts per million is not a tipping point itself—it’s just a benchmark of a complete lack of progress and further crisis beyond anything that was imaginable a few decades ago.”

Climate scientists are hardly complacent. But, Hall says, “it’s very difficult to prove something to be irreversible when we’re on uncharted territory until we’ve passed the tipping point—so, prudent scientists say, it’s like hearing the roar of Niagara Falls before you reach it: you should maybe listen to it and take heed.”

A very different orientation is found in the geopolitical security domain. Here, action is embedded in the strategic register, focused on securing future advantages. Actors include corporations seeking to best competitors under future conditions, and those strategizing to avoid or negotiate regulation—as well as the U.S. military, concerned with climate-induced geopolitical and economic “security threats.”

Strategic denial

A particularly interesting case in Hall’s study is the domain of conservative denialism. This domain somewhat awkwardly fuses a vision of climate change as “cyclical” and therefore natural with a strategic (often economically-motivated) interest in proactively addressing consequences—one that borrows from the “security” paradigm.

Hall explains, as “certain uncomfortable facts on the ground” make themselves felt, even conservative and corporate interests increasingly accept the reality of change. But by explaining change as natural, they deny any need to curtail causal human activity even as they strategize over consequences.

The embrace of strategic action by denialists reveals the limitations of the geopolitical security approach. “It seems on the one hand pragmatic, but on the other hand it accords with climate denialism in that it’s only pragmatic in dealing with the consequences, not with identifying causes and trying to control those causes.”

Apocalypse now?

Environmental activism, the fourth of Hall’s domains, is the perspective most aligned with an “apocalyptic” vision. In some cases, individuals have crossed over from other domains to activist territory. Thus, former NASA climate scientist James Hansen, now party to a lawsuit against the Obama administration for its alleged inaction on climate issues, stepped across this divide.

Prompting some scientists to wade into activism, Hall suggests, is the level of “political intractability” that action on climate change faces. Given such intractability, the apocalyptic orientation has yielded more pessimistic understandings.

The Dark Mountain project, for instance, exemplifies resignation to a cataclysm that is seen as unstoppable, advocating heroic accommodation to an apocalypse already in progress. “At its origins,” Hall notes, “the project is really asserting the incapacity of politics to deal with climate change.”

Rejecting efforts to salvage what is usually defined as the “progress” of modernity (technology, highways, etc.) from destruction by fighting climate change in conventional ways (reducing carbon emissions, etc.), Dark Mountain seeks to adjust to a new life in a changed future already upon us.

The business of risk

Hall remains adamant about the importance of continued social scientific engagement with the subject of climate change. He sees the greatest potential in research that continues to investigate how “climate change” is constructed and addressed in varied institutional settings. Different domains have complexities in need of greater exploration: for instance, some businesses actively seek “green” status, while others strive to avoid regulation. What are the causes and implications of these positions?

As tangible effects of climate change increase in coming years, we will need a critical lens through which to examine social responses. Describing private “risk consulting” companies beginning to offer their services to property owners in Florida, Hall invokes German sociologist Ulrich Beck, whose concept of “risk society” describes the contemporary shift away from public distribution of benefits, and toward individual avoidance of risk. “To the degree that individual avoidance of risk then translates into action,” Hall observes, “it is becoming a privatization of strategic action.”

Serious engagement

A number of researchers are doing innovative work in the social science study of climate, Hall notes. At UC Davis, PhD candidate in Sociology Zeke Baker examines the formation of modern climate science in the context of relations between science and the state. Hall and Baker will present a joint paper on climate change at next year’s conference of the American Sociological Association.

The UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies (ITS) is engaged in valuable work on the future of hybrid and electric vehicles—including contributions from another Sociology PhD candidate, Jennifer TyreeHageman. TyreeHageman examines the influence of consumer-assigned meanings on behavior in the emerging plug-in electric vehicle (PEV) market. Work by ITS and other campus research centers and departments such as the Center for Water-Energy Efficiency, and the Department of Plant Sciences, among others, contributes crucial applied research toward reduction of greenhouse emissions and improved sustainability.

Humankind has the dubious honor of having lent its name to the present geological era—the Anthropocene. Ultimately, finding a sustainable future in the Anthropocene will, as Hall’s analysis suggests, require serious engagement with the social element—both in how we act to affect climate itself, and how we understand and act upon “the climate” as object.

To learn more about John R. Hall, visit his faculty webpage.